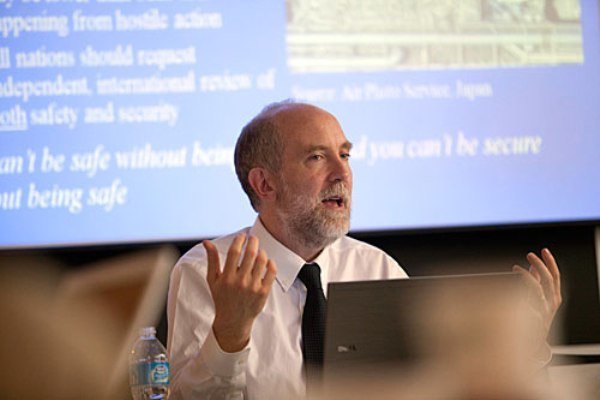

An American university professor and former adviser to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy Matthew Bunn told Mehr News in an exclusive interview that he believed the Republican-majority Congress will reject an Iran deal, but will not be able to override Obama’s veto power.

Here is the full text of interview:

Will US congress revoke nuclear deal with Iran?

When the deal is submitted to the Congress, both the Senate and the House (both of which have majorities of Republicans) are likely to vote against it. President Obama will then veto that resolution of disapproval. The Obama administration is hoping to get Iran to agree to a strong enough agreement that US opponents of the deal will not be able to get the two-thirds majority needed to override Obama’s veto.

Because of this situation, I believe it would be in Iran’s national interest to agree to provisions that would help build support in Congress, including far-reaching transparency and inspections. That is the only way a deal that provides substantial relief from US sanctions can be achieved and sustained.

If US Congress revokes the deal, what will be the internal and external reactions to it? How would that affect Republicans’ position in US presidential elections 2016?

The Republican candidates for president are running against the deal, criticizing it as an example of what they see as a weak Obama foreign policy. If a deal is completed and in place before the next president takes office, however — including a UN Security Council resolution lifting the UN sanctions — it may be difficult (though not impossible) for the new president, whether Democratic or Republican, to rip up the agreement.

If the US Congress revokes the deal, what will be the future of deal?

Congress is likely to vote against the deal, but Obama is likely to veto a Congressional disapproval. If opponents of the deal in Congress do not succeed in putting together the two-thirds majority needed to override the veto, the deal would go ahead as negotiated. If opponents of the deal did put together a two-thirds majority to override the veto, the United States would then not be able to participate in the deal, and it would be very difficult to avoid having the deal collapse.

A longer-term question concerns the next President. If that President is a Republican who does not support the deal, it may still be difficult for him to pull out of the deal. But what will happen if disagreements come up, with the United States claiming Iran isn’t fulfilling all of its obligations, or Iran claiming the United States is not fulfilling all of what it promised? The agreement will be complex, the Iranian and US leaderships will continue to distrust each other, and such disagreements often arise in other nuclear agreements. Both sides will have to work hard to resolve disagreements and maintain the deal — but if there’s a US president (or an Iranian leadership) who opposes the deal, that hard work is not likely to happen, and the deal may fall apart over time.

Overall, I believe it would be in Iran’s national interests to agree to a strong agreement and implement it faithfully, to get broad relief from US, European and other sanctions.

Iran nuclear deal will be ratified as a resolution under chapter 7 of the UN charter. What are the legal implications of it on two sides?

A new resolution would revoke those UN sanctions imposed because of Iran’s nuclear activities, and would likely legally require Iran and others to take some of the steps called for in a negotiated deal. In the negotiations between Iran and the 5+1, the specifics of such a UN resolution have been extensively discussed.

Interview by Javad Heirania

Matthew Bunn is a Professor of Practice at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government. Before coming to Harvard, Bunn served as an adviser to the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, as a study director at the National Academy of Sciences, and as editor of Arms Control Today.

Your Comment