One would think the punchline for any Hamlet revival on the stage would be – as hackneyed as it has certainly become over the span of some 400 years since its creation, but still as indispensable – ‘to be or not to be; that is the question.’ But the question, still as evasive as ever, feels less urgent in Christopher Rüping’s production than Hamlet’s screaming into a microphone, ‘Es war keine Liebe!’, to a petrified Ophelia, played by a male actor, Nils Kahnwald, who was dressed in a simple blue gown, standing still and miserable in the middle of the stage.

Hamlet herself in this particular scene was phenomenal. Nothing short of amazing. Played magnificently by 40-year-old Katja Bürkle, whose shouts of acidic words and gush of fury and vitriol, in that frenzy fever of insanity and loathing, had stolen the breath from the audience who did not dare to blink once, lest they miss an important part, a fleeting expression on Bürkle’s face. ‘Es war keine Liebe!’, Hamlet screamed. It was not love. “I loved you not.”

And just as well, when the performance neared its end, and Hamlet’s all-too-familiar words appeared on the screen flashing and beeping like a bad omen, ‘Sein oder nicht sein’, Hamlet let out a sigh in frustration, as if saying ‘we still have to deal with this question in 2018?’ And she took off her black hoodie, which served to signal that this actor was currently playing Hamlet in mourning, and left the stage, letting the musician to step in and play the recordings of famous historical mimes, who celebrated the quote with pathos. Then the existential monologue gradually turned into the lyrics of some kind of electro music with eerie undertones and a sense of foreboding as each actor took over Hamlet in turn and breathed a new life into the ever nagging question of ‘to be or not to be.’

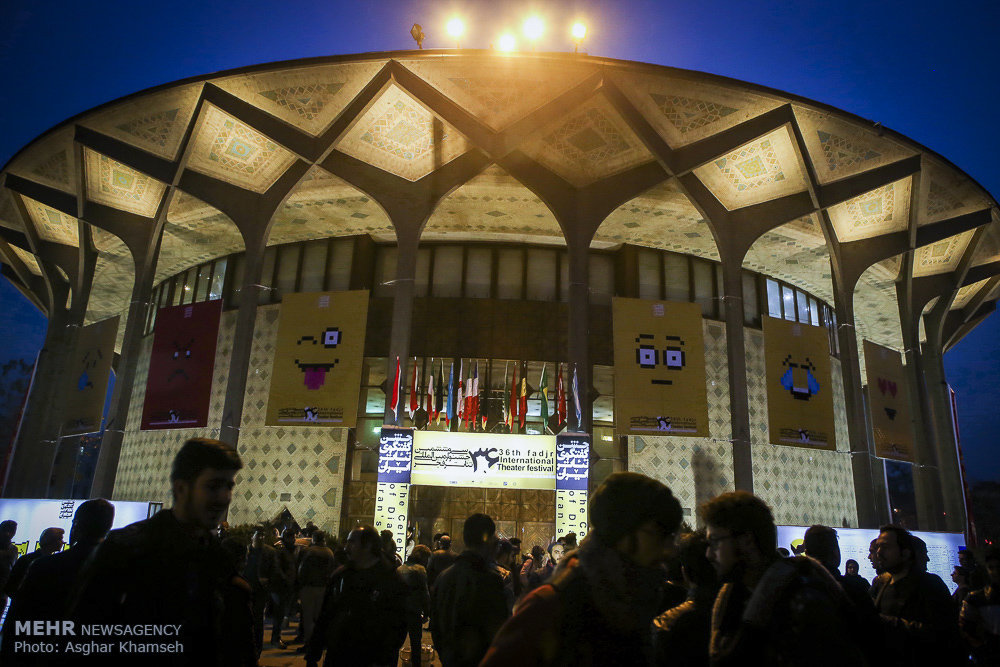

Rüping’s Hamlet opened for the second run on Monday at the 36th Fajr Theater Festival in Tehran to a full house. At the entrance, there were more than a dozen people who did not manage to buy a ticket before all of the three performances were sold out. As soon as they saw someone with a ticket in his/her hands, they would ask if there was an extra ticket they could buy. Some didn’t even get a seat, but would still rather sit on the steps or stand in the corners to see the two-hour play unfold in grandeur and a breathtaking force that was carried well into the very last lines: ‘Prinz Hamlet ist zurückgekehrt in Dänemark.” Prince Hamlet has returned to Denmark.

Let us backtrack to the start, which was not really the start, but the end of the play: Hamlet’s death, the beginning of an end. With the voice of ghost Hamlet coming through a machine, the big brother of sorts, the omniscient, bold texts appearing on a screen, telling his friend Horatio to live on and stay “in this harsh world” for a while to tell his story and make sure people would not forget about him. The audience then became the people that Hamlet wanted to be remembered by, and Horatio, played by all four actors on the stage, began telling the familiar story of betrayal and revenge, but this time with a twist, or perhaps one could say, a more profound stress on a particular characteristic of Hamlet.

No, I’m not talking about his procrastination or indecisiveness. Not even his melancholy or cynicism. I’m talking about his bloodlust.

Bucketful of theater blood was thrown onto the grates that covered the stage and over each actor’s head, signaling their death. Hamlet was drenched in blood to signify his bloodlust, his radicalism, that you wouldn’t be too surprised to see a gun in his hand, going on a killing spree because “etwas ist faul im Staate Dänemark.” Something is rotten in the state of Denmark, and Hamlet considers himself as the chosen one, tasked with the mission to cleanse the world of the rot. Rüping sees Hamlet not as a doubter or a philosopher, but a fanatic; the judge and the executioner; not as a victim but a culprit. A psychopath lusting for revenge, until everyone is dead, including himself.

Fittingly, the world of Rüping’s Hamlet is chaotic, fragmentary and menacing. Bürkle as Hamlet is compelling, formidable and frightening. Amidst the blood and the smoke (and colorful confetti), the tragedy turns on its head and drags the audience up to their feet for a long standing ovation. We are still no closer to an answer for that 400-year-old existential question, but somehow it does not seem to matter. I leave the auditorium with Hamlet’s scream of ‘Es war keine Liebe!’ ringing into my ears.

Last year, Germany participated at the Fajr Theater Festival with Thomas Ostermeier’s Hamlet, again to a full house for all its three runs. It went on to win the festival’s Grand Prix, and deservingly so. Interestingly enough, the festival’s Grand Prix for its 2014 edition also went to Hamlet, this time by an Iranian stage director Arash Dadgar. Hamlet, as it seems, means a lot to the Iranian theatergoers and critics alike. It remains to be seen whether Rüping’s Hamlet will also be lucky to be the third of its kind to win Fajr’s Grand Prix. Third time’s the charm, and all.

Your Comment