Taliban forces have made significant progress in Afghanistan over the past week and have captured almost all of Afghanistan from the Afghan National Defense Security Forces (ANDSF). The successive fall of the Afghan provincial capitals to the Taliban, not with heavy weapons, fighters and helicopters, but with individual light weapons, once again stunned the world.

Some military and political experts believe that behind-the-scenes gangs and some groups within the government were involved in the downfall of the cities. According to the estimates of Western governments and American generals, who were the founders of the Afghan army in the early years of the twentieth century, in the best case, these forces would have to resist for up to six months without foreign aid, and in the worst case, for three months.

The available data set on the current developments in Afghanistan emphasizes that weakness and internal conspiracy can not be considered only as of the main cause of the early collapse of the Afghan army and the government of Ashraf Ghani and ignored the decisive role of the Americans.

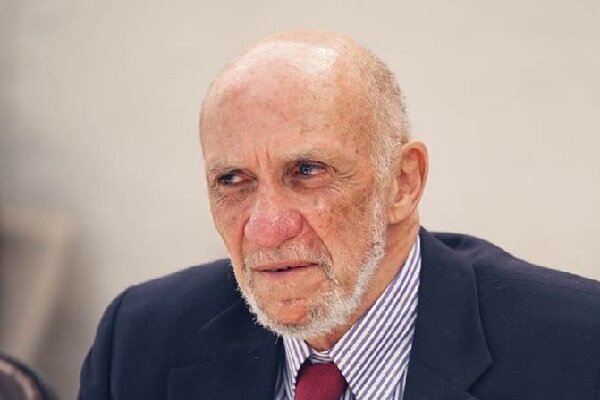

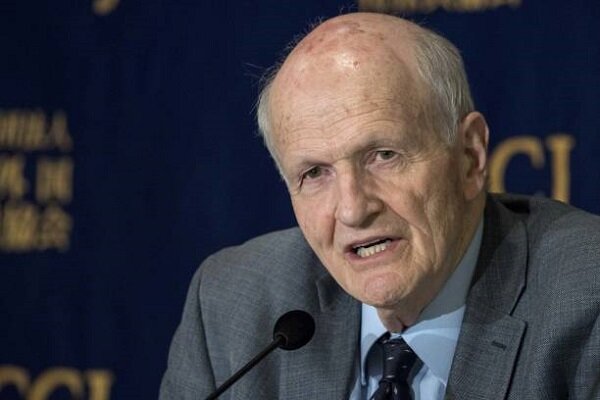

To shed light on the reason behind the fall of Afghanistan and the role of the US during this period, we reached out to Professor Richard Anderson Falk, an American professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University and former UN official and Professor Frank von Hippel, an American theoretical physicist, and a Professor of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University.

Following is the text of the interviews with Prof. Falk and Prof. von Hippel in which they shared their views with MNA audiences:

Why could the Taliban capture Kabul and gain power so rapidly without considerable resistance from people and the army?

Falk: The US led NATO Afghan intervention and occupation was flawed from its outset in 2001, and indeed in the period before that. In the post-colonial world, the military superiority of Western intervening powers has proved unable to shape the political outcomes of a prolonged struggle for the control of non-Western sovereign spaces. In Afghanistan, as elsewhere, this observation proved correct, despite trillions of dollars spent in devastating parts of the country and supposedly building armed forces and police capabilities capable of bringing order and stability to the post-Taliban governance process.

The fundamental explanation of the rapid collapse of the Kabul government is that it had no legs of its own to stand upon. Afghan collaboration with the intervenors was largely left to opportunists, corrupt politicians and private sector entrepreneurs, and ambitious careerists, as well as the alignment of some ethnic groups, and the support of secularized social elites in the larger cities. The Taliban despite its abysmal human rights record during its five year period in power at the end of the last century never lost its credibility as a defender of the Afghan homeland and retained the loyalty of many nationalist elements in this essentially religious country.

The unexpectedly quick collapse of the Kabul government so painfully constructed by the Western intervenors over a twenty-year period of occupationIn explain the unexpectedly quick collapse of the Kabul government so painfully constructed by the Western intervenors over a twenty-year period of occupation, Taliban reassurances of peace and reconciliation undoubtedly further weakened whatever will to resist survived the American military withdrawal. These reassurances included proclaiming the end of the war for control of the country, amnesty for those who worked in and on behalf of the Kabul government, promises of the protection of the rights of women, tolerance of diversity, and pledges not to allow its territory to be used in the future as it was in the past as a base for projecting terrorism beyond its borders.

Yet the basic explanation of the unexpectedly quick collapse of anti-Taliban resistance also reveals the political misjudgments of the United States despite 20 years of experience in the country. It obviously did not appreciate that its investment in the Afghan army and police force failed to create even the semblance of a countervailing force to that at the disposal of the Taliban. Had Washington realized this vulnerability to collapse, it would handle its own withdrawal differently, getting its Afghan collaborators out while it still could control the main cities.

von Hippel: I was surprised as anyone by the rapid collapse of Afghanistan’s military. My guess is that they had more confidence in the NATO military forces in Afghanistan than in their own government. The NATO military forces had drawn down to about 10,000 troops but there were in addition about 20,000 contractors supporting the Afghan air force as maintenance technicians, providing security for the embassies, etc. When this support structure was withdrawn, the Afghan military lost the confidence to fight.

Afghanistan’s military had more confidence in the NATO military forces in Afghanistan than in their own governmentThat suggests that Afghanistan’s military leadership did not earn the confidence of its own troops and/or did not have confidence in the government. It also suggests that the US military did not understand or did not inform the US political leadership about how fragile the situation was. This is very similar to what happened in Vietnam where the US military always promised the political leadership that, after another year of effort, South Vietnam’s military would be able to stand on its own feet.

I don’t understand why the population did not pick up the arms that Afghanistan’s military laid down and fight the Taliban itself. It is hard to understand how any population would be willing to submit to such fanatics. If the local populations had been more willing to support Afghanistan’s military, perhaps the military would have fought better.

How do you assess the US policy in Afghanistan during the past 20 years? To what extent the US policy is responsible for the current instability in the country?

Falk: To some extent, my response to the prior question covers these issues. The idea of intervening in a non-Western state in the post-colonial era should have been discredited long ago. The success of the anti-colonial movements in Asia and Africa should have demonstrated to the West that military intervention on the basis of acceptable costs in lives and resources was no longer a policy option, however great the temptation. The result of such missions impossible is devastation, widespread human suffering, so-called ‘forever wars,’ and an eventual ‘intervention fatigue’ by the American public and leadership that is expressed by a growing political consensus that the undertaking, whatever its ideological or imperial The Idea of intervening in a non-Western state in the post-colonial era should have been discredited long agomotivations, is not worth the effort. It is too costly and the geopolitical payoff, if any, is too obscure to justify killing and dying. Because American lives and taxpayer dollars were increasingly seen as wasted, the resulting political failure is disguised by the leadership with a lame rationale that convinces almost no one except a compliant Western media. It is rejected, including by returning American soldiers who felt cheated, understanding that their patriotic sacrifices were in vain even misguided and that the whole imperial venture had been built on delusions and lies.

The reason that these patterns of failed interventions continue, oblivious to this record of failure arises in part from an absence of moral and political imagination needed to comprehend the changed international circumstances of the 21st century. This absence includes the refusal to learn from China about how an ambitious state should go about expanding and heightening its prosperity along with its regional and world influence in a post-colonial era. In part, this failure is systemic. It is associated with the bureaucratic and entrenched interests in the United States that benefit from a high defense budget and a militarized approach to security, which in turn depends on exaggerating, and even inventing, international threats and hiding the global shift in the balance of forces from geopolitical intervenors to national forces of resistance motivated by an ethos of self-determination as the most basic of human rights.

von Hippel: Afghanistan was unstable when the US came in. It was being run by fanatics whose social model was more than a thousand years old and who were opposed by local “warlords.” The US put great efforts into strengthening the society, including empowering and educating women but was unsuccessful in fighting corruption and the importance of opium growing to the domestic economy.

US put great efforts into strengthening the society, including empowering and educating women but was unsuccessful in fighting corruption This failure contrasts with the success of the US after World War II in turning Germany, Italy, Japan and South Korea into economically successful democracies. But Germany, Italy and Japan were modern societies before World War II that could generate their new leaderships for the rebuilding process. Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan were not and the US was overconfident that it could both fight corruption and supply what was missing.

How do you see the future of Afghanistan? What US approach should be taken toward the country in future?

Falk: It is very difficult at this time so soon after the Taliban victory to anticipate the future of Afghanistan. It will depend, first of all, on the behavior of the Taliban as the governing force, and how this is portrayed in and manipulated by foreign countries, especially in the West. The US, in particular, will likely maintain a very critical attitude partly to continue the myth that its intervention was justified was based on good intentions and the attempt to make life better for the Afghan people. The Taliban will also react in terms of its perceptions as to whether the US has genuinely respected the outcome of the struggle, becoming respectful of Afghani sovereignty, and does not launch attacks or impose sanctions. After all, Afghanistan was victimized by two decades of intervention, and will naturally give a high priority to defending the security of the country and its governing process.

US, in particular, will likely maintain a very critical attitude partly to continue the myth that its intervention was justified and based on good intentions and the attempt to make life better for the Afghan peopleThere is bound to be some hostile propaganda from a growing and aggrieved Afghani refugee community, which might be manipulated by American militarist and reactionary forces to restore political will in the United States, reviving its reputation as a self-confident custodian of global security. It is instructive to look back at the behavior of the United States in the decade after its withdrawal from Vietnam in 1975 under somewhat similar circumstances when it tried, among other evasions of defeat, to sell the hysterical idea that the alternative to fighting in Vietnam for the American people was to fight its enemies within American territory.

The best approach for the United States, although unlikely, is to encourage Taliban moderation by exhibiting deeds and words an acceptance of the outcome in Afghanistan. This could be expressed by a rapid grant of diplomatic recognition of the Taliban as the legitimate representative of the Afghani people in all international arenas, and a commitment to provide significant amounts of humanitarian assistance. It is also important that departures from Afghanistan should be handled in a non-provocative manner, stressing humanitarian responsibilities, and appreciating that many of those departing from Afghanistan partook of corruption and opportunism during the American presence.

In the wider context of international relations, I would hope that the failures of the US approach to Iran ever since 1979 would at last lead the political class in Washington to switch its tactics from confrontation to accommodation. It is never too late for this to happen. I wish I could conclude my responses by expressing the belief that it will happen in the near future. I am not presently hopeful.

von Hippel: It is hard for me to see how the US can do much to help Afghanistan develop under the Taliban leadership. I think we owe help to those Afghanistan citizens who have joined the modern world and who manage to escape Taliban control – either to the Kabul airport or over the borders. But I fear that many – especially women and children – will be trapped and lose hope in their ability to pursue better lives. It is a terrible tragedy.

In addition, the US is concerned that Al Qaeda and/or other terrorist groups will be hosted by the Taliban again. But, with communications interception, drones, etc., it should be possible to target such groups from outside the country.

Interviews by Zahra Mirzafarjouyan

Your Comment