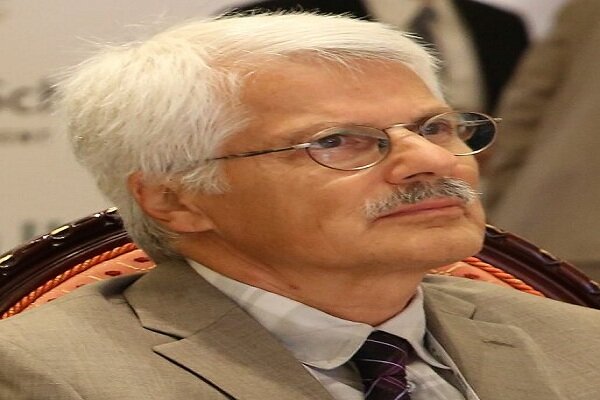

“As I have shown in my blog and in other writings, if properly measured, living standards in Iran are now about 60 percent higher than in the 1970s,” Djavad Salehi-Isfahani said in an interview with the Tehran Times as Iran is marking the 41st anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

Salehi-Isfahani has every now and then criticized the way Iran’s economic development is underestimated by ordinary people, the media, and even economists.

He says by using the wrong metrics it has been claimed in a BBC Persian article that living standards are now 30 percent lower.

“There is no place that I know where data is more important for clearing things up than in Iran, where many people make comparisons based on hearsay,” says Salehi-Isfahani, who is also a Nonresident Senior Fellow at Global Economy and Development at the Brookings Institution.

The professor says before the revolution the government mainly focused on urban areas.

“Before the Revolution, public policy was urban biased. Rural areas grew but the public investment was mainly diverted toward urban areas. As a result, the main source of poverty and income inequality, which was the rural-urban gap, remained unchanged.”

However, he says, after the Revolution “poverty reduction became a focus of state policy” and the ruling system shifted its focus on rural development.

The transcript of the interview is presented below.

Dr. Salehi-Isfahani, as we approach the 41st anniversary of the Islamic Revolution, a very important question still remains hotly disputed, which is whether Iranians are poorer or wealthier today compared to the pre-Revolution era. What tools – statistics, formulas, etc. – should we use so as to find a correct answer to this question?

The most important comparison is in living standards. There is no place that I know where data is more important for clearing things up than in Iran, where many people make comparisons based on hearsay. I often hear very educated Iranians in the US speak of how good things were before the Revolution. One person put is in these words: “Before the Revolution people had their home, a car, and one trip abroad every year. Who can do that today?” These erroneous statements are easy to refute. We know from survey data that in 1972 only 6 percent of Iranian families owned a car, compared to 48% today. And with more than half the population living in rural areas before the Revolution, the idea of everyone traveling abroad once a year seems very silly.

But more systematic comparisons are available. To do this, we need to add up all the value of all the goods and services that the average Iranian consumes. This is what GDP accounting does. However, this accounting is complicated by the fact that prices and qualities of goods and services change over time. So, it is critical to correct for inflation, which is done routinely, and to adjust for improvement in quality, which is done less often. For a country like Iran, it is also important to adjust for differences in the cost of living. Vast subsidies in Iran, especially to energy, after the Revolution, do not get counted properly in the accounting of GDP. Subsidies cause Iranian prices to be much lower than in other countries. Most services, such as housing and health, also cost less in Iran than in, say the US, because they are not tradable.

For these reasons, the value-added generated by sectors whose products are priced lower than in the US underestimate the level of consumption, and therefore the standard of living, in Iran relative to the US This is why economists do not use the market exchange rate to compare total value added (the GDP) in different countries. Instead, they use exchange rates that equalize the cost of a standard basket of goods. This is called the Purchasing Power Parity exchange rate, which several international organizations compute for all countries, including Iran. Unfortunately, many researchers who work on living standards and poverty in Iran do not use PPP rates and obtain very negative pictures of economic growth in post-Revolution Iran. As I have shown in my blog and in other writings (read “The Islamic Revolution at 40” and “Iran’s economy 40 years after the Islamic Revolution”), living standards in Iran are now about 60 percent higher than in the 1970s. Using the wrong metrics, it has been claimed in a BBC Persian article to be 30 percent lower!

You mentioned how some Iranians living abroad compare the living standards between pre- and post-Revolution eras. The question is how one’s socio-economic class affects the way he/she judges this issue.

Not easy to answer. Many educated people can overcome their class background and look at the world more objectively.

Now, what are the wrong tools usually used, either intentionally or unknowingly, to figure out whether Iranians are now poorer or wealthier?

Using constant price series without accounting for the fact that subsidies have grown over time is one source of errors people make in GDP comparisons. There are also more intentional use of indicators, like a BBC Persian report that showed how much gold a teacher can buy before and after the Revolution (read my analysis of this claim: “The gold standard to measure change in household welfare in Iran”), and another one claiming that the minimum wage before the Revolution could buy 7 times as much meat as today (read my comment: “Fact-checking the meat consumption of Iranians”). These comparisons like to claim that they offer more accurate measures of individual welfare than GDP per capita, but they fail to keep the standard of accuracy in such comparisons. For example, in the gold comparison of wages, they ignore the fact that gold prices have increased globally, and a similar comparison would suggest, incorrectly, that US teacher wages are also much lower than they were in the 1970s.

How would you evaluate the impact of economic and financial sanctions on Iran’s economy and the population’s living standards?

It is clear in my view from the GDP per capita series in PPP, which shows Iran’s living standard rising until 2011 and then it is stagnant, as shown in the graph in the piece referenced earlier. I do not know of a better explanation for the sudden change in the performance of Iran’s economy than sanctions. All other issues that people raise – mismanagement, corruption, etc. – existed before and after. I am not denying that these other problems exist, but sanctions are the most obvious explanation.

Now, let’s move on to economic policy. What policies were adopted during the Shah’s era and how did they impact poverty?

There was very little in terms of policy or indeed public attention to poverty before the Revolution. Talk of poverty was the exclusive domain of the opposition to the Shah. The focus was on economic growth, which almost always reduces poverty. Poverty must have fallen significantly in the 15 years before the Revolution because economic growth was robust. Since poverty reduction was not the target of policy, there was very little written about it. There were one or two papers that had published results on income inequality but none on poverty. Despite rapid economic growth in the 1960s, by 1971 the poverty rate was quite high, estimated at 54% according to an unpublished study by Ginneken (1980). The oil price increase reduced this rate further to 28% in 1975. You can see the trend in poverty before and after the Revolution in my article “Iran’s economy 40 years after the Islamic Revolution”.

Before the Revolution, public policy was urban biased. Rural areas grew but the public investment was mainly directed toward urban areas. As a result, the main source of poverty and income inequality, which was the rural-urban gap, remained unchanged.

What about the policies adopted after the Revolution?

After the Revolution, poverty reduction became a focus of state policy. Chief among the policies was the shift in public investment toward rural areas, mainly under the leadership of the Jahad-e Sazandegi (Construction Jihad). Extension of roads and the electricity network, followed by schools and health clinics, narrowed the rural-urban gap in income and contributed to improved poverty and inequality.

Later on, in 2010, the introduction of cash transfers further reduced poverty, but this reduction was pure redistribution and was in contrast to the policy of rural investment which reduced poverty through economic growth and without much redistribution.

Later on, after 2013, inflation sharply reduced the real value of cash transfers and poverty climbed back on, from less than 10 percent (with $5.5 PPP) to about 15% today. The new policy of increased cash transfers will for a while reducing poverty, but without economic growth and more employment, it is hard to be very optimistic about long term improvement in the welfare of lower-income families.

What does the Human Development Index (HDI) tell us about how things have changed for the Iranian people in the past forty years?

It shows that Iran has done well in terms of health and education. Iran’s HDI was slightly above that of Turkey until a few years ago, despite the fact that Iran’s per capita income is 20% lower. Unfortunately, in 2019, with sanctions taking their toll, we fell a few places below Turkey.

MNA/TT

Your Comment