Our theme for this year – chosen by the United Nations Environment Programme – is perfect: “Seven Billion Dreams. One Planet. Consume with Care”.

UN Secretary-General Mr. Ban Ki-moon says: “There is no ‘Plan B’, because there is no planet B.” He is right. Earth is the only home we have.

This is a message that both inspires and warns. And the warning relates to the “human security” challenges that we all face.

The concept of human security equates security with people rather than territory – with development rather than arms.

So, human security has many elements – community security, health, economic, personal, political, food and environment. All of these are concerned with how human beings live and feel “secure”. We all need to breathe clean air. We all need to drink clean water. We all need to be safe from the elements. We all need to be able to take care of our families and sustain our livelihoods.

So, one of the most important elements for the state to secure is the very environment in which its citizens live.

But these days – in all our talk about security – how much time do we actually devote to what is perhaps the greatest existential threat to our security? And this is the threat coming from an environment that has been exploited by humans and is – rightfully – angry with us. Here in the Middle East this will increasingly be manifested in a hotter drier climate.

The plain fact is this. Planet Earth does not need human beings. It is we who need Planet Earth. The environment is no longer – if it ever were – merely a “green” issue. It is cannot be considered a luxury item on the national agenda. It is now a security issue. Pure and simple. A “human security” issue. And what is ultimately under threat is our human civilization.

Take water. Water may sustain lives. But clean, safe, drinking water is what defines civilization.

But, globally, water shortages already affect 2 billion people in over 40 countries. Projections show that by the year 2050, water stress will affect 54 countries. These countries are currently home to 4 billion people. This is well over half the world’s population. True, water is a renewable resource. But our current consumption has exceeded its carrying capacity. That’s the global picture.

Now let’s turn to Iran. Same story. While the per-capita water resources of Iran stood at 7,000 cubic-metres-per-capita-per-year in 1956, today, the figure is less than 1,900. This is the threshold for “water shortage”. On current trends this situation will worsen. According to current modeling, by the year 2020, the figure will decline further, reaching the “water scarcity” threshold of 1,300 cubic-metres-per-year. These are government projections.

Water is vital for our daily lives. We cannot live for more than a few days without water. Our health is directly dependent on water. We need water for agriculture and to feed ourselves. Water is a vital element of our industry and our economies.

Perhaps the two most visible water-related challenges we face in Iran are Lake Urmia in the Northwest and the Hamoun Wetlands in the Southeast of Iran. I have had the privilege of visiting both – and many other water hotspots across the length and breadth of this amazing country.

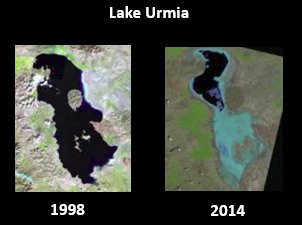

Take a look at these two satellite images comparing the health of Lake Urmia in 1998 and 2014. The black part represents water. Notice that since the mid-1990s, the lake has lost over 90 per cent of its water. During the intervening period, the amount of land in the Urmia basin used for agriculture has doubled. People are also cultivating plants which require 6 times as much water. You can see for yourself what is the result.

Take a look at these two satellite images comparing the health of Lake Urmia in 1998 and 2014. The black part represents water. Notice that since the mid-1990s, the lake has lost over 90 per cent of its water. During the intervening period, the amount of land in the Urmia basin used for agriculture has doubled. People are also cultivating plants which require 6 times as much water. You can see for yourself what is the result.

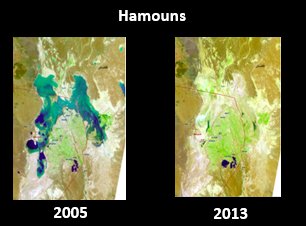

Look now at the other end of Iran – to the Southeast of Iran where the Hamouns lie. Here are two satellite images of the Hamouns in 2005 and 2013. This time the blue part on the left represents the water. Notice how, slowly and steadily, you can see that the waters from the Helmand River, which used to feed the Hamoun, have been blocked off upstream – in both Afghanistan and Iran. Now there is no water. No fish for the fishing communities to catch. Little employment, since local residents’ traditional means of livelihood was all water-based. More than half the inhabitants get by on welfare delivered through state charities. They live amid the decayed ruins of ghost-like villages built on the side of once-thriving lakes.

Look now at the other end of Iran – to the Southeast of Iran where the Hamouns lie. Here are two satellite images of the Hamouns in 2005 and 2013. This time the blue part on the left represents the water. Notice how, slowly and steadily, you can see that the waters from the Helmand River, which used to feed the Hamoun, have been blocked off upstream – in both Afghanistan and Iran. Now there is no water. No fish for the fishing communities to catch. Little employment, since local residents’ traditional means of livelihood was all water-based. More than half the inhabitants get by on welfare delivered through state charities. They live amid the decayed ruins of ghost-like villages built on the side of once-thriving lakes.

When people’s livelihoods are threatened – including because of a lack of access to water, they become desperate. All of these changes will prompt movement of people. And when people move, they become vulnerable. Environmentally displaced people migrate to places where resources still exist. Places like where you and I live. They move to seek a better life. They add pressure to new areas. This pressure is not sustainable in the long run. It causes more insecurity. It can drive people to lawlessness and violence. It can threaten human security.

We are starting to see this pattern all across our planet. Environmental migrants and refugees will also become one driver of human insecurity in the Middle East in the future.

So, there are really only two points I would like you to reflect on after reading this article.

First, we need to fix what we have broken.

Second, in order to do this, we need to change how we think about and understand security. The way we talk about it. We need to embrace the concept of “human security”. And in this, we need to prioritize environmental security. I have spoken and written elsewhere with many suggestions on how we can fix some of our environmental problems in the region.

The thing is, we all have a role to play. Governments. International organizations like the UN. NGOs. You and me.

It would be easy for me to suggest to you a laundry list of things to do. But instead of that, I will only ask that you ask yourself what role you can play and where.

Can our engineers, for example – or the city planners among us – or architects – design our surroundings to make them greener and more sustainable? Will our statesmen and stateswomen – and our politicians – be prepared to take the tough decisions required to save the planet – including at and after the forthcoming Sustainable Development Summit in New York in September and the Paris Climate Change Summit in December?

Which businessmen will act to improve the environmental impact of their operations? Will you and I discuss environmental security over the dinner table with our children? And will we change our own behaviour accordingly – recycling our trash, saving water, planting trees, using less fossil fuels?

We all have a role. Let’s go back briefly to the story of Lake Urmia in Iran.

In the UN, we are working with the Government of Iran at the national and provincial level – with local communities, NGOs – and particularly with farmers – and with the help of one far-sighted donor-partner country. The essence of the solution is to work with farmers to use better techniques to consume less water.

The water thus saved will become available to refill the lake and increase the ground water levels in the basin. This will probably not restore the lake to the stage that it was in the 1990s. But it can be restored to some level of environmental viability.

We have shared problems. So we must seek shared solutions.

We need to stay positive. These things can be fixed. There is a role for everyone.

As human beings, while we have become the masters of the planet, we have also become the terror of our ecosystem.

It is now up to us to mount a great heroic quest to protect our human security.

Together we can save Lake Urmia, the Hamouns and our environment. Let us recognize that this is also the only way to protect our future.

So let’s mount this great heroic quest. All are welcome. All hands count.

Gary Lewis is UN Resident Coordinator in the Islamic Republic of Iran

Your Comment